Brilliant Lives

by John W. Arthur

Published by the author in 2024

First published in Great Britain in 2016 by

John Donald, an imprint of Birlinn Ltd

Copyright © John W. Arthur 2016, 2024

All rights reserved.

Contents

16 Lewis Campbell and Peter Guthrie Tait

We can hardly move on without saying something about the lives of James Clerk Maxwell’s closest friends from their schooldays together at Edinburgh Academy. James was best man at Lewis Campbell’s wedding while Tait was the man he addressed as O.T. on the halfpenny postcards that the two of them exchanged when they had some point of physics to discuss. Campbell was a classicist who had taken the prize in mathematics and had been school dux[1] in 1846, while Tait and Maxwell took prizes in mathematics but had never been overall dux. And so, in the way of young people, they were the best of friends and at the same time the best of rivals. There were no grudges between them, even later in life when it came to Tait being preferred over Maxwell for the chair of Natural Philosophy at Edinburgh.

16.1 Lewis Campbell

Lewis Campbell was born on September 3, 1830, at 13 Howard Place, Edinburgh. From The Life of James Clerk Maxwell we know that Campbell’s mother was actually a Mrs Morrieson:

…a journal kept by my mother, then Mrs Morrieson, in which she occasionally noted matters relating to her sons’ friends. (C&G, p. 132)

We also find in Memorials in Verse and Prose of Lewis Campbell (Campbell & Campbell, 1914) that Mrs Morrieson had been born Eliza Constantia Pryce (1796‒1864), hailed from Gunley in Montgomeryshire, and that she had a fair reputation as a poet (Roberts, 1908). Her first husband had been Capt. Robert Campbell RN, governor of Ascension Island from 1819‒23, but he had died in 1832 leaving her with two very young sons, Lewis and Robert, to fend for by herself. She worked hard to put her sons to school, latterly at the Edinburgh Academy which Lewis had attended from 1840, just a year before James Clerk Maxwell arrived on the scene. It may be presumed that she put her talents as a writer to good use in this endeavour, for in 1833 she published a book, Welsh Tales, which also had a separate Scottish edition in 1837. Eventually, the then Mrs Campbell remarried in 1844 to Lt. Col. Hugh Morrieson, of the 20th (Bengal) Native Infantry, who had retired from service in the East India Company in 1841 (Asiatic Journal and Monthly Register, 1841).

As to where they lived, Lewis tells us:

— somewhere in 1843 or 1844…my own closer intimacy and lifelong friendship with James Clerk Maxwell began … Shortly after this we became near neighbours, my mother’s new domicile being 27 Heriot Row, and we were continually together for about three years. (C&G, p. 55, my emphasis)

Coincidence of coincidences, 27 Heriot Row was the very house owned by James Clerk Maxwell’s great-uncle Lord Newton, and in which his great-aunt Bethinia had lived until 1842. Morrieson was the next name to appear at number 27 in the Edinburgh postal directories, from 1843 until 1859, whereafter the entry was Mrs Hugh Morrieson right up to up to the year of her death in 1864. Indeed, Hugh Morrieson had died in 1859 and was buried beside his brother Robert in the ‘Covenanter’s Prison’ section of Greyfriars’ Churchyard. For several years, a Robert Morrieson lived at 6 Heriot Row, but as yet we have no direct evidence of a connection, only the suggestion. Before we leave the Morriesons, however, we find that in The London Gazette for the 9th February 1855, pp. 163‒4, Hugh Morrieson was posted as a retired full Colonel. On the same page, at the top of the next column is posted Thomas Wardlaw of the same regiment. Both men had returned from service in the East Indies about the same time and from 1844 lived within yards of each other given that Colonel Wardlaw and his wife became the tenants at 14 India Street. We may guess that they had been close friends and wished to remain so.

Lewis Campbell went to Edinburgh Academy in 1840 and was already in Mr Carmichael’s class when James Clerk Maxwell joined it in November 1841. His friendship there with James Clerk Maxwell (and Peter Guthrie Tait )has already been mentioned in §2.2, including him spending a holiday with James at Glenlair in the September of 1846. His brother, Robert, two years younger and also at Edinburgh Academy, visited Glenlair in the year following. It is clear that James and the two Campbell boys were close friends indeed.

Having excelled at Edinburgh Academy, as did his friends,, Lewis went to the University of Glasgow in October 1847.[2] Although he and they were now going their separate ways, they continued to keep in touch; Lewis and James exchanged many letters from which we get illuminating glimpses of their lives, and according to Campbell’s widow, Lewis continued to visit James at Glenlair during further summer vacations. At Glasgow, Lewis read classics and took the Blackstone Medal for best in Greek in 1849. He then went to Oxford where won a Snell Exhibition Scholarship to Balliol College. His academic successes continued with a first in ‘Greats’, that is to say classics, in 1853 and within three years he was made a Fellow of Queen’s College where he became a tutor; in addition, he was ordained as an Anglican priest. For reasons that will soon become clear, it is worth mentioning that one of his pupils at Queen’s was John Percival, who became Bishop of Hereford and Principal of Clifton College near Bristol.

In 1858 Campbell was appointed as the vicar of All Saints Church at Milford-on-Sea, Hampshire, where he married Frances Pitt in May of the following year, with Maxwell making the long trip down from Scotland to be his best man. The newlyweds were soon to follow James’ journey back to Aberdeen to attend James’ own wedding to Katherine Dewar. While at Milford, Campbell coached students for university entrance, one of whom was Charles Hope Cay (1841‒69), son of Robert Dundas and Isabella (Dyce) Cay (§14.7). Since he was James Clerk Maxwell’s first cousin and Milford-at-Sea was a place quite far out of the way, it would seem that the recommendation that he should go there to study with Lewis Campbell must have come from Maxwell himself. It produced the desired result, for in 1860 Charles won a classics scholarship to Caius College Cambridge. Interestingly, in 1864 he became a mathematics master at Clifton College, where Campbell’s old friend, John Percival mentioned above, was the rector.

A significant change came for Campbell when in 1863 he was elected to the chair of Greek at the University of St Andrews where James D Forbes, relative and former mentor of James Clerk Maxwell, was Principal. While there, he started a dramatic society for the benefit of the students. His old school friend Charles Fleeming Jenkin (1833‒55) (see §2.7n65) had been appointed to the first Regius Chair of Engineering at the University of Edinburgh in 1868; both Fleeming and his wife were keen amateur actors and took an active interest in the productions staged by the society. Campbell was also a supporter of further education for girls and, after some years of campaigning in this direction, St Leonard’s School was opened in St Andrews in 1877. After James’ death in 1879, at the request of his widow Katherine he began work on The Life of James Clerk Maxwell. Not being sufficiently grounded in science, he concentrated on Maxwell’s life while his chosen co-author, William Garnett who had been Maxwell’s demonstrator at the Cavendish, wrote the account of his scientific work. The first edition was published in 1882 with the second following in 1884.

Having been a good teacher well respected by his students, Campbell retired from his St Andrews chair after nearly thirty years in post and moved to London in order to concentrate on his literary work. A committee was organised to come up with a fitting commemoration, the result of which was the Campbell Memorial Medal awarded to the best finalist in Greek, a prize which is still awarded to this day. His retiral did not last long, however, and he returned to St Andrews in 1894 and 1895 as Gifford Lecturer.

Campbell was in the habit of taking his family on summer vacations in Italy, with the ulterior motive of spending much of his time studying ancient classical manuscripts in Florence’s Laurentian Library, and in 1898 he decided to move there permanently, making his home, aptly called Sant’ Andrea, at Alassio on the Italian Riviera. He never tired of working and eventually died at the age of seventy-eight at Lake Maggiore; he was buried thereafter at the English Cemetery in Locarno, Switzerland. In the time that had passed since the death of his dear old friend, James Clerk Maxwell, he must have had much pleasure in hearing of the discovery of electromagnetic waves and of the emergence of wireless telegraphy. He wrote in an essay criticising Ivan Tolstoy’s biography of Maxwell :

… yet his electro-magnetic theory of light was undoubtedly the precursor of the Rontgen rays… and wireless telegraphy is an application of ideas on which he used to discourse to me. (Huxley, Criticism of Tolstoy, 1914, p. 386)

Beyond that, in his final years he may well have heard early reports of emerging atomic theory and of Albert Einstein’s baffling theory of relativity. If so, he would surely have taken note of two things – firstly, the questions they posed for conventional religious notions about the nature of the Universe and, secondly, the name of his friend being attached to their origins. Einstein himself readily acknowledged that he had drawn his inspiration from Maxwell’s electromagnetic theory.[3] How Campbell’s admiration for his old friend must have turned to the profoundest sense of wonder!

16.2 Peter Guthrie Tait

Just two months older than James Clerk Maxwell, Peter Guthrie Tait was born in Dalkeith, a county town about ten miles to the south-east of Edinburgh (O’Connor & Robertson, 2003; Knott, 1911). In 1837, not long after beginning his education at Dalkeith Grammar where long before some of the young Clerks had studied, his mother Mary was widowed. She, Peter and his two sisters then moved to Edinburgh to live with their uncle, a Mr John Ronaldson, who was a writer and, by profession, a banker. At the time John Ronaldson lived at 25 East Claremont Street on the eastern fringe of the Second New Town, but between 1845‒6 they all moved to Somerset House on St Mary’s Place, a section of Raeburn Place on the west side of present day Stockbridge, Plates 15.1 and 15.2.

Plate 15.1 : Somerset Cottage on a plan of about 1850

Houses and shops have long since lined both sides of St Mary’s place.

Plate 15.2 : Somerset Cottage in 2015

In the 20th C. the building was better known as the Raeburn Bar and Hotel. Once a fashionable watering hole, it became sadly run down before being refurbished and reopened as popular modern hotel and restaurant. The frontage seen in the photograph is probably little changed from when it was Peter Guthrie Tait’s home.

To the north and west of Somerset House lay open fields and parklands, while to the east was the village of Stockbridge that straddled the Water of Leith at the northern fringe of the Second New Town. In fact, the south-eastern edge of Stockbridge still runs along India Place, which of course almost connects with our better known India Street at NW Circus Place.[4] The location would have been convenient for Peter attending Edinburgh Academy, which he began in 1841, for it is just a ten minute walk away[5] from Somerset House (or Cottage, as it later became known). In 1847 he matriculated at Edinburgh University along with his friend James Clerk Maxwell. Things would have been much less convenient for his journey to the Old College involved trekking over to the other side of town. After just a year there, however, he left for Peterhouse College, Cambridge, where he took his BA in 1852 and became Smith’s prizeman and the youngest senior wrangler then on record.[6]

Having stayed on at Cambridge until 1854, he left for Belfast to take up the chair of mathematics at Queen’s College, Belfast. While there he married Margaret Porter, whose brothers had been friends of Tait’s at Cambridge. It was also while at Belfast that he took up an interest in quaternions, the work of William Rowan Hamilton.[7] Quaternions proved to be the foundation of vector algebra, and Tait did much to promote their use and later published a treatise on them (Tait, 1867).

In 1860, however, he returned to Edinburgh on getting the Chair of Natural Philosophy, thereby disappointing James Clerk Maxwell in his attempt to land what would have been a very convenient post. Had Maxwell been successful, 14 India Street could once again have become his winter home, and by then he could well have travelled from Edinburgh to Glenlair in a day. As things turned out, it was the successful applicant, Tait, who needed to find an Edinburgh home. From 1862‒67 he lived at 6 Greenhill Gardens which, until 1864, made him a neighbour of Jane and Robert Dundas Cay, who were at number 19, just a two-minute walk away. He would surely have remembered his old school friend’s Aunt Jane and called on her. Likewise, it would have been very convenient for James, for he could easily call on both Peter and has Aunt Jane when visiting Edinburgh during that period.

Not long after taking up his chair at Edinburgh, Tait formed the idea of writing a sort of magnum opus on mathematical physics, and having written most of the first volume he was joined in his efforts by Sir William Thomson, later Lord Kelvin, who was well known to both Tait and Maxwell[8]. It took until 1867 to get the first, and only, published volume into print (Thomson & Tait, 1867; O’Connor & Robertson, 2003)

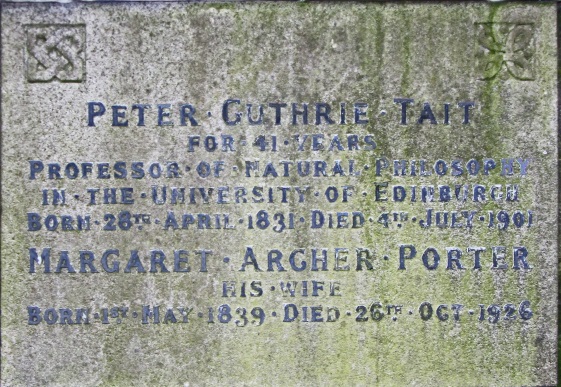

From Greenhill Gardens, the Taits moved to 17 Drummond Place, which is in the Second New Town near the east end of Great King Street (whereas India Street is closer to its western end), but after a few years there they moved in 1873 to 38 George Square, which was undoubtedly much more conveniently situated for the University, and there he spent the rest of his days. He died in 1901 and was buried on the higher level of the north-east corner of St John’s churchyard .

Peter Guthrie Tait had four main influences on James Clerk Maxwell

- When they were at school, he was a great encouragement to the fledgling mathematician in Maxwell. By rivalry, they both pushed themselves higher, by collaboration, they learned much each from the other

- All through their adult lives, they corresponded with one another, carrying on a briefer but perhaps more focussed and equally rewarding dialogue

- Tait specifically persuaded Maxwell to incorporate quaternion equations, that is to say, a proper vector formalism, in his Treatise on Electricity and Magnetism. To be fair, Maxwell did not abandon the original form of his original equations, the quaternion form was introduce as an alternative without comment as to what Maxwell thought about them

- When they were both looking for suitable academic posts in 1860, Tait sealed Maxwell’s fate by beating him to the Edinburgh chair. Had things been otherwise, Maxwell would never have been at King’s, he possibly would not have retired for a spell to Glenlair, and latterly may have been too settled at Edinburgh to take on the Cavendish.

Plate 15.3 : Professor Peter Guthrie Tait’s Memorial Stone

It lies within a small family plot in St John’s churchyard at the southeast corner of Princes Street and Lothian Road, Edinburgh.

John Ronaldson had died around 1864 but Peter’s sisters were still at Somerset Cottage in 1900.

While it was his old school friend Lewis Campbell that wrote his biography in The Life of James Clerk Maxwell (C&G herein), it was Tait, who was asked by the RSE to write his obituary (Tait, 1879‒1880). As the following extract shows, as opposed to the usual form of flattering valediction one might expect to find in such a piece, he spoke honestly of Maxwell:

But the rapidity of his thinking, which he could not control, was such as to destroy, except for the very highest class of students, the value of his lectures. His books and his written addresses… are models of clear and precise exposition; but his extempore lectures exhibited, in a manner most aggravating to the listener, the extraordinary fertility of his imagination.

We may therefore take his final words on Maxwell as nothing less than the very truth:

Scotland may well be proud of the galaxy of grand scientific men whom she numbers among her own recently lost ones; yet … she will assign a place in the very front rank to James Clerk Maxwell.

16.3 Notes

[1] Dux meaning leader, that is to say, he took the overall school prize in his final year

[2] Campbell & Campbell (1914) has it wrongly as 1846.

[3] While Maxwell’s electromagnetic equations played a central role in Einstein’s theory of special relativity, it is often overlooked that it was Maxwell’s use of the field concept to account for the mediation of forces through both matter and empty space that struck him most deeply (Thomson, et al., 1931, pp. 66‒73; Einstein, 1954).

[4] As mentioned elsewhere, India Street was built on a level much above NW Circus Place, so that access from the one to the other is by a flight of stairs. Just around the corner from the stairs, India Place terminates on the same level as NW Circus Place. By either route, Tait could call on Maxwell and Campbell at their homes on Heriot Row more or less as conveniently as he went to school.

[5] Via the old bridge over the Water of Leith from whence Stockbridge took its name.

[6] http://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Tait,_Peter_Guthrie_%28DNB12%29

[7] Professor of mathematics at Trinity College, Dublin, as distinct from the Sir William Hamilton, Professor of Logic at Edinburgh mentioned in §2.3.

[8] In their correspondence, they referred to themselves as respectively T, T’ and dp/dt which was a sort of in-joke referring to symbols commonly used for temperature (T), a second temperature variable (T’), and a thermodynamic formula, dp/dt = JCM (Maxwell’s initials). For James at least, his schoolboy sense of fun still endured.